📹 Downloading a browser video stream into an MP4

Turning an HLS stream into an MP4 using browser tools and ffmpeg.

I recently wanted to download a wedding video from a media-hosting platform that had no download button. If my browser could play it, the video data was clearly being streamed somewhere; how hard could it be to capture and save it as an MP4?

Turns out: not very hard. With chrome://media-internals, DevTools and an (AI-generated) ffmpeg command, I went from a streaming HLS video to a local MP4 file in about 15 minutes.

Step 1: Is this thing encrypted?

I wanted to know whether the browser was dealing with encrypted or DRM, which would complicate matters quite a bit. On Chromium-based browsers you get a useful tool for that: chrome://media-internals.

I opened that page, then played the video in another tab. A new media entry appeared. For kVideoTracks, the value was:

[

{

...

"codec": "h264",

"coded size": "1920x1080",

...

"encryption scheme": "Unencrypted",

...

}

]

and for kAudioTracks:

[

{

"bytes per channel": 2,

"bytes per frame": 4,

"channel layout": "STEREO",

"channels": 2,

"codec": "aac",

...

"encryption scheme": "Unencrypted",

...

}

]

In other words:

- Video codec:

h264(High profile), 1920×1080. - Audio codec: AAC stereo.

- Encryption scheme:

Unencrypted.

So no encryption! Also, no Content Decryption Modules to worry about.

In contrast, if I play something on netflix.com (which uses Widevine for DRM), the encryption is listed as "encryption scheme": "CBCS" and kIsCdmAttached: true in chrome://media-internals.

Step 2: Find the stream URL in DevTools

Next task was to get the master manifest file. I went to the tab playing the video and opened up DevTools → Network.

I started playing the video and filtered the requests by .m3u8. This was a guess, though a likely one, since most Web video content uses Apple’s HLS protocol for adaptive video streaming. I was looking for a master manifest file: a top-level manifest that lists all available quality options for a video. On playing the video, one URL popped up that looked like a master manifest file:

https://media.website/videos/o.m3u8

Clicking on the master manifest and looking at the response showed:

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-VERSION:6

#EXT-X-INDEPENDENT-SEGMENTS

#EXT-X-MEDIA:TYPE=AUDIO,GROUP-ID="program_audio_0",LANGUAGE="eng",NAME="Alternate Audio",AUTOSELECT=YES,DEFAULT=YES,CHANNELS="2",URI="o_2ch-160.m3u8"

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=6599291,AVERAGE-BANDWIDTH=4657683,VIDEO-RANGE=SDR,CODECS="avc1.640028,mp4a.40.2",RESOLUTION=1920x1080,FRAME-RATE=23.976,AUDIO="program_audio_0"

o_1080p.m3u8

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:BANDWIDTH=1694319,AVERAGE-BANDWIDTH=1347730,VIDEO-RANGE=SDR,CODECS="avc1.640020,mp4a.40.2",RESOLUTION=768x432,FRAME-RATE=23.976,AUDIO="program_audio_0"

o_432p.m3u8

This master manifest essentially says: “Here are two quality options you can choose from: 1080p or 432p. Both use the same audio track. Pick whichever fits your bandwidth.”

It doesn’t contain any media segments itself.

Step 3: Piping the master manifest into ffmpeg and downloading

Amazingly, the URL for the master manifest is all that ffmpeg needs! It can figure out the rest (downloading the manifest, reading it, picking a video quality variant, fetching the relevant playlists, downloading the media segments, remuxing) once it has the master manifest file 🤯

An initial naive effort was just taking the request URL for the master playlist and passing that to ffmpeg.

ffmpeg -i "https://media.website/videos/o.m3u8" -c copy video.mp4

Note: The -c copy tells ffmpeg to not re-encode the audio/video samples and instead simply remux the H.264 + AAC streams into MP4, so it saves us a lot of time and processing. I’m actually not sure why it’s not the default; it might be because ffmpeg is primarily a transcoder, though I’m not well-versed enough with ffmpeg to say more here. Update: this quickstart guide is useful if you’re looking to getting into video editing.

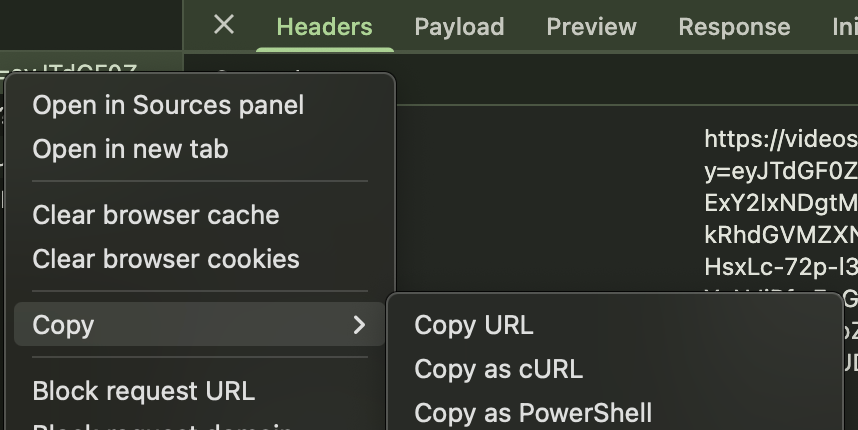

Unfortunately, the ffmpeg command above didn’t actually work; the server blocked it as “403 Forbidden”. That makes sense since I had to login on my browser to play the video file. Fortunately, pretending to be the browser is pretty easy. DevTools has a handy Copy as cURL option for network requests (just right-click the request and go to Copy >). This gives you all the cookies and headers sent by the browser for the network request.

I could have spent some time massaging the cURL command into what is accepted by ffmpeg but I was too lazy so I just asked ChatGPT to do it for me and it one-shotted converting cURL HTTP cookies into ffmpeg’s headers format:

ffmpeg

-headers "Cookie: CloudFront-Key-Pair-Id=abc; CloudFront-Policy=def; CloudFront-Signature=xyz"

-i "https://media.website/videos/o.m3u8"

-c copy test.mp4

And that’s it. ffmpeg got to work and figured it all out for me.

End result: a portable MP4 video file that plays everywhere! This was ~simple because:

ffmpegas a tool is super useful (if a bit ornery) if you’re doing anything related to audio/video.- Browser developer tooling is extremely good and worth familiarizing yourself with.

- No DRM or encryption or complicated authentication; this wouldn’t work for Netflix/Disney+ etc.